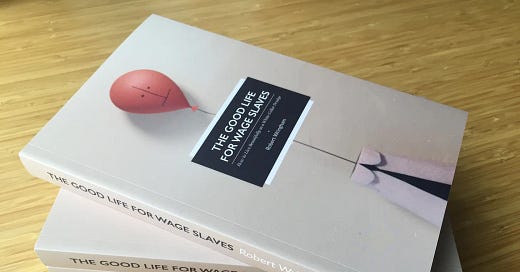

The Good Life for Wage Slaves

New Book!

As you'll already know if you're a reader of New Escapologist, I have a new book out. It's called The Good Life for Wage Slaves: How to Live Beautifully as a White-Collar Drudge.

I'd like to encourage you all to buy it directly from the publisher so that she doesn't lose money on the project and regret the day she ever clapped eyes on me.

It's available as a deluxe paperback with fancy little jacket flappies or as a soulless ebook if that's your sterile, heartless bag.

*At this point, the publisher takes Wringham quietly by the elbow and whispers something into his ear.*

A hundred percent, you say? Hey, buy buy that ebook everyone! I always loved ebooks. You can't stand in the way of progress I always say.

Ahem.

In the tradition of Escape Everything! and New Escapologist itself, the new book is a humorous-but-serious critique of modern work and consumerism. It is also, as we've told the press, my final word on these subjects before I hole up and write short novels.

Novels, Mr. Wringham? Yes, madam, novels. It's what I've been building up to this whole time. One can't just sit down and knock out Catcher in the Rye with absolutely no thought or preparation.

Because Salinger already did that. *spins bow-tie*

In the meantime, however, there's The Good Life for Wage Slaves. I hope you enjoy it. There's an excerpt below for your delectation. It's not a work-oriented excerpt and instead comes from the second part of the book, which is about home life and has, I feel, the mercurial tone appropriate to this mailing list. Here goes. *clears throat*

One chilly January evening, perhaps looking for a way to banish the darkness or perhaps just a way to ignore my deadlines, I bought a violin.

It was £20 on eBay and it came with its own case, bow, sheet music and some oils for maintaining its violinny sheen. It had been listed for auction by a mother whose daughter had not the discipline to learn the instrument and had lost interest. Two can play at that game, I thought. I can try, fail and lose interest as good as any child. It’ll be back up on eBay before you know it.

To be honest I had no interest in learning how to play the violin. I just wanted to make a noise and to ponce about Escape Towers in my dressing gown with a Stradivarius tucked beneath my chin like Sherlock Holmes. Nobody needed to know this detail. It could be my own little secret.

“I’ve just bought us a violin!” I announce to Samara when my phone makes the sound that indicates a PayPal transaction has been made.

“Is that so you can be like Sherlock Holmes?” she said.

“No,” I said.

But it was also just a good way to have fun, idly, without the television or YouTube. How Bohemian it would be! I wouldn’t look at the sheet music save to marvel at its indecipherable, arachnid-in-the-inkwell beauty, but instead simply lie upon the chaise and, touching horsehair to horsehair, see what happens.

A bloody din is what happens. A bloody, marvelous din. There is nothing wrong with this. It is good fun to “play” an instrument as a naive, without even the slightest pretense that one will “master” it or even become competent.

It’s funny how often we hear that technical skill in painting has not been essential to art production since the invention of the camera but that we practically never hear that musical accomplishment went out of the window with the synthesizer or, for that matter, the phonograph. Even the punks valued two or three chords. I don’t even know what a chord is, which is why I am the true king of contemporary music.

On a walk one afternoon, I noticed a sparrow chirping while sitting on a metal railing. The railing was evidently a system of hollow tubes and I got the distinct impression that the sparrow was using the railing to amplify his chirps. No musical training there. Let us all be small sparrows capable of making big noise.

As a teenager, I asked (and to my surprise was given) an Alto saxophone for Christmas. I’d requested it in the wrong spirit, genuinely thinking that I might learn to play it on top of studying for exams, working a Saturday job, holding ideas about becoming a writer, dating, and (my priority if we’re being honest) watching hours and hours and hours of Star Trek. An entry in my teenage diary shamefully explains that I wanted the saxophone in order “to be like” Grover Washington Jr., a musician I must have been impressed by at the time but whose music in fact I’ve barely listened to as an adult. The saxophone sat in my bedroom in a fancy stand, collecting dust, until I discovered minimalism in my twenties and tearfully sold it. This put an end to what had ceased to be a musical instrument and had become a sculpture dedicated to hubris, laziness and lack of talent. The sax had been acquired in the wrong spirit: a spirit of vanity and hubris. The violin, however, cheap and cheerful, had been acquired simply to mess about with. Magnificent.

Though I have no idea how to play, I sometimes take a deep breath and attack the violin as if I’m about to play the theme tune to The South Bank Show and only drivel comes out. Sometimes I can delude myself into really believing that the theme tune to The South Bank Show will come out of me and the disappointment is palpable. It’s a sort of safe slapstick, like falling downstairs but without getting hurt. Other times, I start slowly, with a sort of wistful romance in my heart as if I’m about to play to newlyweds in a restaurant only for the sounds of Hades to come out. Sometimes I get lucky and produce a sound that might pass as actual music, albeit for only a few seconds, prompting my wife to come running in and say “what the hell was that?”

It does not matter if we’re shitty at playing an instrument. It’s just for fun. It’s a way to add the dimension of music -- okay, of sound at least -- to the home without it being commercially produced by faraway professionals with whom we have no real relationship. Surely this is where the origins of folk music lie: to make sound in a space. It need not be a punishing regime of embarrassing and expensive lessons or of squinting into a patronising, spiral-bound book in the hopes of one day, a decade or so from now, being able to pluck out “Three Blind Mice.”

Let’s just make a noise, for in the morning we’ll be dead. Or back at work, whichever comes first.

And not a single neighbour has complained. Once, at a party, we met someone who played in the strings section of the Glasgow Symphony Orchestra. “That’s interesting,” I said, “I too play the violin.” I thought Samara would never recover.

When I had that saxophone, I’d shown it to my grandad who wistfully confessed that he’d never touched a musical instrument before. He seemed genuinely regretful. “But you have that kazoo,” I offered, to which he gave me a withering look that that “get real.” One could not compare a plastic novelty to a horn of brassy magnificence. The second-hand violin is a very happy halfway point; neither an uninspiring novelty toy nor an intimidating machine of Heaven. You have to stand up to get a sound out of a saxophone. You can fiddle in repose.

All of this is to say that no house should be without a musical instrument. Even a kazoo -- or the similarly minimalist harmonica or stylophone -- is better than nothing. And if (and when) you fail to play it or fall out of love with it or stop wanting to be like Sherlock Holmes (or Grover Washington Jr.) it can be returned to the Great Material Continuum via eBay. Little lost. Much gained. Creative richness and idle silliness, all acoustic and, as such, with no hard corners on which to hurt ourselves. It’s like a sort of softplay for adults.

That's all for now. Please buy the book. I think you'll like it. And if you don't, you can always re-gift it at Christmas to someone you really don't like. It's win-win!

Your friend,

Robert Wringham

www.wringham.co.uk